Want to transform lives with us? Stay in touch and hear about our news, activities and appeals by email!

Why is disability still waiting for real progress on inclusive climate action? Five takeaways from COP27

The Sharm El-Sheikh COP27 Climate Change Conference wasn’t the easiest of times, with various global issues such as conflict, the cost of living, human rights, security and other tensions between stakeholders very apparent.

There were achievements as well as disappointments (see Cat Pentengell’s thoughtful reflection – Bond Website) – but what progress, if any, was made on disability inclusion in climate action?

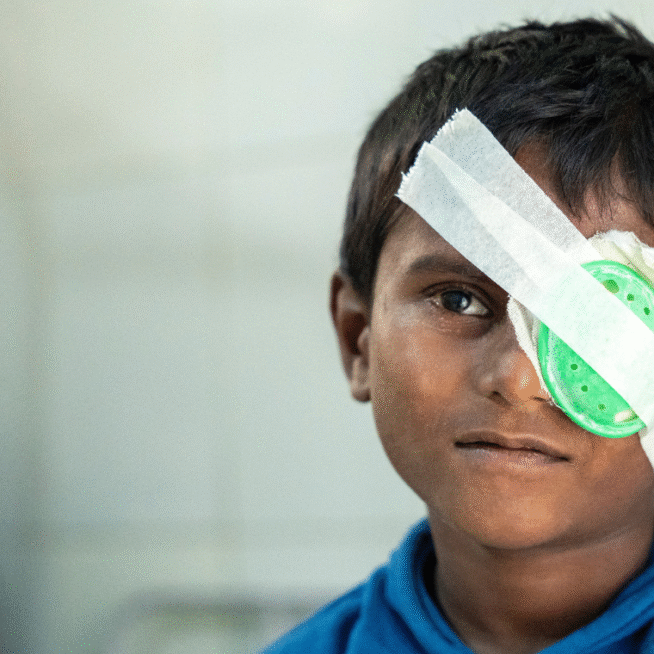

Around the world, one in seven people has a disability, making people with disabilities one of the largest minorities in the world. Despite being among the most impacted by climate change, people with disabilities and their representative organisations are frequently excluded from the decision-making processes and plans to address climate change.

For the Bond Disability and Development Group (DDG) this is an area of priority, and before COP26 in Glasgow we released a briefing paper highlighting the fact that, without including these one billion people in the global climate response, the change sought would not be achieved (Bond Website).

But whilst the understanding of the necessity of including marginalised and impacted groups is growing, interactions with organisations of persons with disabilities (OPDs) and other disability focused organisations who were at COP26 and COP27 demonstrated the huge gap to close before there is full recognition.

With this background, here are five takeaways on disability inclusive climate action which emerged from Egypt:

1. The Loss and damage agreement could have a huge impact for the most marginalised

The last-minute agreement for a Loss and Damage Finance Fund was hailed as “a new dawn for climate justice”. This is a step towards making sure that those countries and communities which contribute the least to climate change, but bear the biggest impact, are properly provided for.

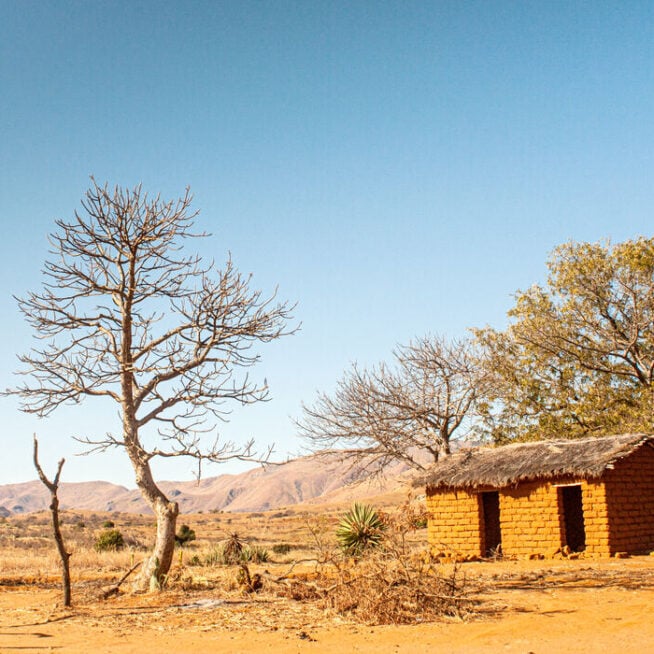

The hope is that when climate disasters happen, with no opportunity or ability to adapt, funding will be available for those communities to respond to their needs. For people with disabilities this is potentially life-saving as they are most often among those living in the most vulnerable areas and require specific funding for recovery.

2. Disability inclusion needs to be accepted by all sectors

The overarching goal of Action on Climate Empowerment (UNFCCC Website) is to enable all members of society to engage in climate action. The wording of the plan, agreed at COP27, specifically mentions people with disabilities (UNFCCC Website).

This tiny, but significant recognition is hopefully a sign that, in future, States will use the UNFCCC process to respond to calls for explicit wording relating to disability inclusion within all climate decisions, policies and processes. Without this specificity the needed coherence on inclusion will not be possible.

3. We need actions, not just words.

There was also recognition by some governments, UN agencies and other stakeholders of the need to do more, including the UK Government.

At a disability-focused side event (YouTube) co-hosted by CBM UK Debbie Palmer, FCDO Energy, Climate and Environment Director stated, “The FCDO strongly supports disability inclusive climate action and we are committed to stepping up this work over the coming years”, acknowledging this as an important emerging area in the new FCDO Disability Inclusion and Rights Strategy (PDF: 46GB).

It is time for all governments to now include rights-based disability inclusive measures in their National Action Plans and policies on climate change to ensure the needs of people with disabilities are met in climate action.

4. It’s not just about accessibility, but it does include accessibility.

Disability inclusion recognition has progressed in recent years. COP27 saw the highest number of people with disabilities and their representatives attending as delegates and speaking at events. However, the start base was very low, with continued barriers to attending in person, inaccessibility of certain areas of the site, and lack of accessible communications.

It was frustrating to still see basic issues such as toilets that were anything but “accessible” and multiple hazards that were both dangerous and preventable. Moreover, unlike Youth, Women and Gender or Indigenous People, Disability is not yet officially recognised as a caucus or constituency, and whilst advocacy being done by a number of us with the UNFCCC to rectify the situation, these factors continue to limit meaningful engagement for people with disabilities. It displays a lack of acceptance within the process.

5. Protecting and funding the most vulnerable must become a higher priority

While some momentum has been generated towards the inclusion of persons with disabilities, the majority, namely those who live in low income countries at the front line of the climate crisis, remain largely outside of all relevant decisions. Funding that is fit for purpose, and supports realistic and appropriate needs-based delivery to those who require it most, including people with disabilities, must be prioritised.

2023 must be the year that climate action properly includes and meaningfully engages with people with disabilities. Everyone should ask, in the climate dialogues, seminars and conferences building towards COP28, “Are people with disabilities properly represented and recognised in this space?”. If the answer is “no” then the call for “climate justice” remains hollow.