In May, I was fortunate to be able to visit our ongoing project, supporting quality integrated inclusive education and eye health in Masvingo Province of Zimbabwe, funded by CBM UK.

Changing lives through education and eye health in Zimbabwe

These life-changing projects are improving access to eye health services and education by targeting children and young people who are already in school and those who are out of school. The project includes community awareness raising, identification and assessment of learners with low vision, refractive errors, and provision of assistive devices, to increase the number of children with disabilities enrolled in schools and to maintain this, as well as establishment of inclusive education resource centres (for learners requiring additional support).

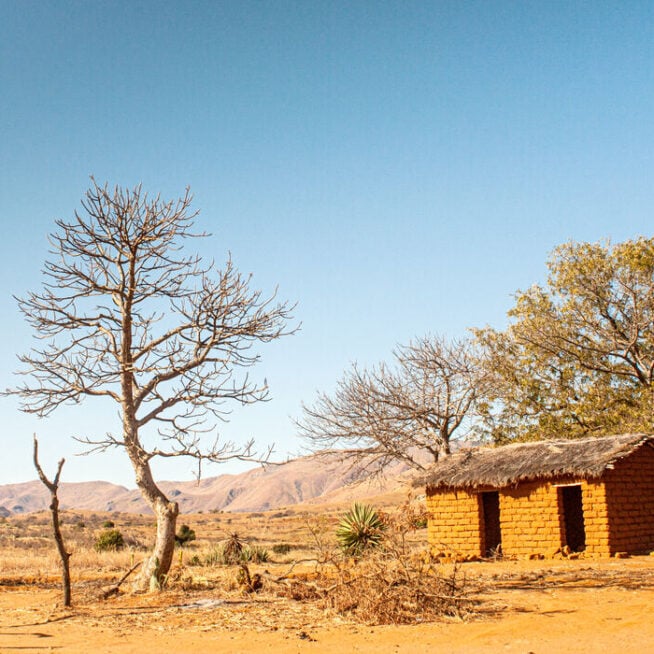

When I first arrived in Zimbabwe, I was struck by the incredible scenery and mountains. The mountains were formed of rock, with most having balancing rock formations. It was beautiful to look at, but I soon learnt the challenges that this geology caused.

Day 1

My first full day in Zimbabwe was focused on meeting with the CBM in-country team, and the project partners: Leonard Cheshire Disability Zimbabwe (LCDZ), and the Zimbabwe Association for the Visually Handicapped (ZAVH), who were visiting the projects with us.

The plan for the week was to see all seven model schools, the local eye clinic, and witness an eye and ear screening outreach at another school. We were prepared for a busy week!

Day 2

Day 2 threw us straight into the project, with a visit to Morgenster Eye Clinic in Masvingo, a four-hour drive from the capital, Harare. The team were able to show us around the clinic and identify the resources that were funded by the project, such as a refraction kit, which is used to determine whether you have a refractive error (a need for glasses or contact lenses) – we later got to see this in action in the outreach screening on day 7.

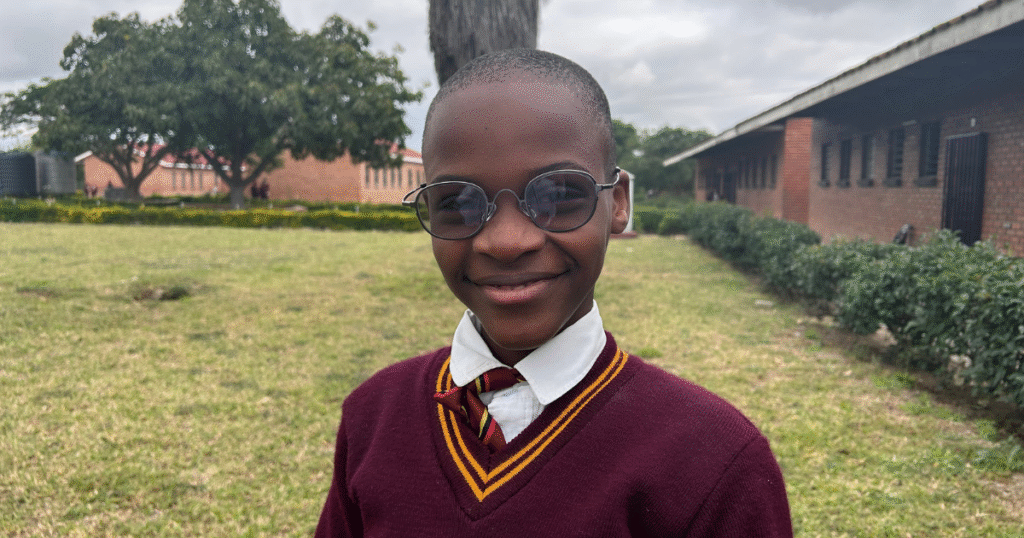

Before we visited our first model school, we made a quick stop at the high school attended by Tinotenda, who featured in our ‘Every Girl, Everywhere’ campaign in 2024. Last year, Tinotenda was in primary school and needed a pair of glasses. Now, she has her glasses and is excelling in school. She was thrilled to see us again and told us she wants to be an artist when she grows up!

From here we travelled not too far to the first of our model schools. We toured the school and saw the accessible resources provided by the project, including assistive devices, a TV for visual learning, health and hygiene resources and the infrastructural changes that were implemented, including making all classrooms and toilets accessible through ramps and wide paths.

As we travelled around the district, we learnt that the beautiful rocky landscape was a huge challenge for local people living here. The rocks meant there was limited to no space to grow produce due to there being no accessible ground to plant in. The ground lower down was better for growing produce, and areas for cattle to roam. This presented challenges not only for people living with disabilities to get around their houses and local communities, but also to grow produce to support themselves.

Day 3

Day 3 introduced us to some off-roading; we travelled over an hour to the Gutu district, where we turned onto a dirt road. The road was bumpy, rocky, and narrow. I couldn’t imagine having to travel down it in a wheelchair, as some students would have to. At the school, we saw the income-generating projects that were initially funded by the project and are now in the school’s hands to use and grow, developing a source of income. This particular school bought chickens, which the pupils tended to. Some schools would sell the chickens or the eggs to buy more livestock, such as goats.

From Gutu, we travelled towards Bikita district, about an hour away, to visit the third of the model schools on our list. This school had put in some impressive accessible walkways, and I loved the addition of black and white stripes to the edges, it made me feel like I was on a racetrack; although I hope the children in wheelchairs don’t use it for speeding around the school! The accessible modifications the school had made were impressive, and it was wonderful to see how they were supporting children living with disabilities.

Day 4

On day 4, we headed to two further model schools. At the first school, we were able to see the income-generating project that they had implemented: sheep and goats. The animals had had a successful year, and their numbers had grown dramatically, showing great care and investment. We could see firsthand how our initial investment in the project helped them to overcome the barriers of finding sources of income, and a way of bringing the pupils and community together with the school. From caring for the animals to selling them within the local community.

From here we travelled to the Chivi district, around an hour away. One thing that stood out to me from this school was how knowledgeable the headteacher was with his students. The headteacher was able to tell us about how many children with disabilities they have, how their test results have risen in recent years, and how they have implemented the project. The infrastructure changes were clear to see, with walkways now flat and clear, and ramps into the classrooms, making it much easier for children with disabilities to move around the school.

Day 5

On day 5, we travelled for over three hours to the next model school. The road to the district was under construction, and with only long diversion routes as an option, we tackled the rocky and tough terrain of the road to get to the district. It would have been impossible without a suitable car. Here, I met a little girl named Kupa, aged 9, and her mother. Kupa has cerebral palsy and received a wheelchair as part of the project’s assistive devices distribution. Kupa told me that when she grows up, she wants to be a doctor. She is top of her class and is performing incredibly well in all subjects. I knew from her determination and confidence that she could achieve what she dreamed of, and with her mother, school and CBM supporting her, there were numerous opportunities that had opened up for her.

As we toured the school with Kupa and her mother, we could see why it was so important for the school to improve its infrastructure. The classrooms were only accessible via steps as they were raised off the ground. The new ramps installed meant Kupa could get into her classrooms with ease.

Day 6

On day 6, we visited the last of the model schools, in Zaka district, just under two hours away from Masvingo. At this school, we saw two bikes which had been purchased as part of the project. These bikes are used by village health workers to travel to the houses of those who have children with disabilities who have either dropped out of school or are not attending. The aim is to try and reach out to them to find a way to get these children into school.

Day 7

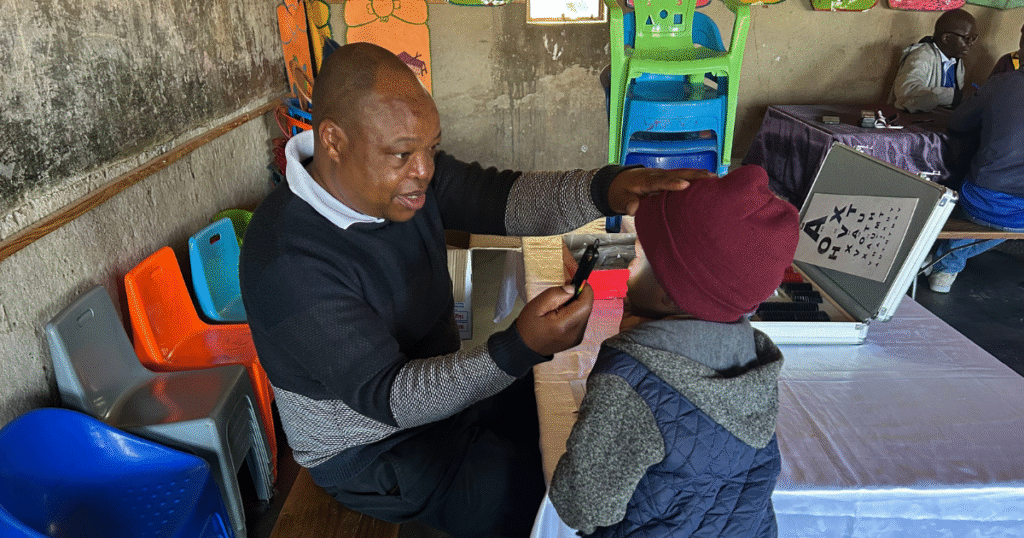

On day 7, we were staying locally in Masvingo city, attending the outreach screening at a local school, held by Morgenster Eye Clinic. At the outreach, we witnessed hundreds of children being screened for eye and hearing problems. Firstly, they were given an initial eye check where they had to stand covering one eye at a time and see how small of letter they could identify on the chart, like what they do here in the UK. Then they were sent to the ophthalmologist for an eye screening using the Arclight, which is an affordable and portable ophthalmoscope that only costs £13 and is seen to be dramatically improving eye care in low- and middle-income countries.

Once they were screened, their results were recorded, and they returned to class. There were several children who had allergies affecting their eyes and received eye drops. We saw a few children have refractions, where the ophthalmologist used the refraction kit to test the children’s eyes further. Some children were referred to Morgenster Eye Clinic for further examinations, and others were fitted for glasses then and there. For the children that were referred, I was glad that we were at a local school, knowing they didn’t need to travel far to the clinic for further treatment. It took less than an hour to get to the clinic. But for the schools further away that required transportation, I knew there would be difficulties faced by some families to be able to get to the hospital. I could see the importance of bringing eye screening to schools; without it, many children would go undiagnosed or untreated.

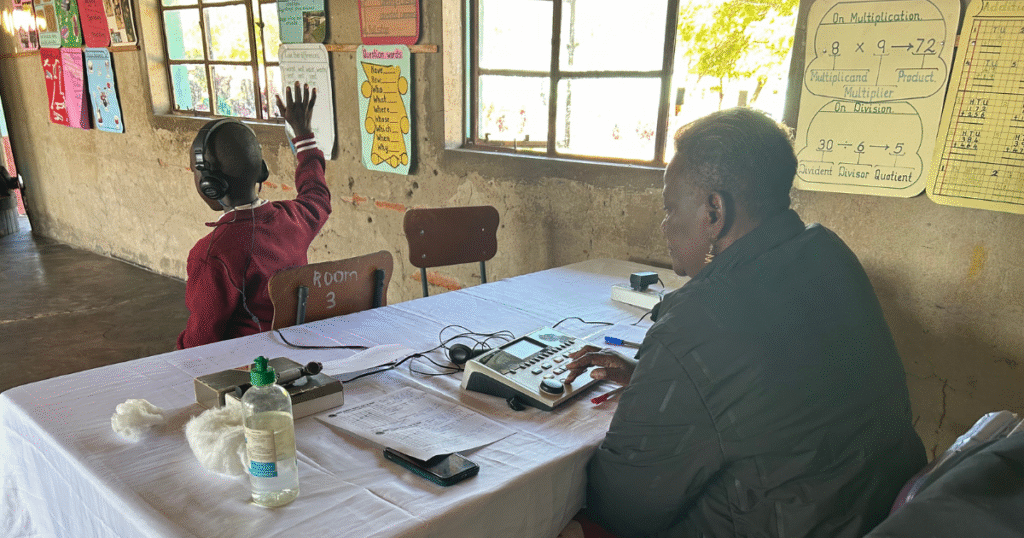

Across the other classrooms, the audiologist was performing hearing tests on children. The children wore headphones and were facing away from the audiologist. When they heard the sound, they were asked to raise their hand to indicate they could hear it. Numerous children were identified as needing hearing aids in both ears, which is funded by the project. Knowing that these children would have the opportunity to stay in school and not be excluded or limited by their disability was empowering to see, and knowing the schools were committed to keeping the children in school, and understanding the importance of disability inclusion was inspiring.

After a long and busy week, we returned to Harare to wrap up the visit with a meeting with the country team, debriefing on everything we’d seen during the trip.

My time in Zimbabwe was inspiring and eye-opening. From meeting all these inspiring students, like Tinotenda and Kupa, to seeing our work in action at the eye screening, I was able to witness how our supporters are changing thousands of lives across Zimbabwe.